![]()

Victorian Cooking: Receipt vs Recipe

Victorian Cooking: Receipt vs Recipe

The following citation comes from a familiar cookbook–the one that covered the “true history” of Angel Food Cake. Several ‘recipes’ cited in the past week or two have been labeled “receipt”. So, which is it? Receipt or Recipe?

Jessup Whitehead, author of The American Pastry Cook, answers this question:

Which is right? Worcester says that a recipe is a receipt for cooking; also, that it is a formulary [sic] or prescription for mixing certain articles, particularly in medicine. Webster, also, makes recipe and receipt appear nearly synonymous terms, and attaches to the former a particularly medical meaning that is nowhere made to belong to the other…. The French recette, which appears to be the original of our receipt, is pronounced like it; and yet all the translated French books have recipe instead. Of half a dozen different articles on the grocer’s shelves, four have recipes printed on the packages while others have receipts. Of six persons talking together, four or five will say recipe, the rest receipt. The label on the bottle tells you that the sauce beside your plate was prepared from the receipt of a nobleman of the county. But the nobleman’s only authoritative English cook-book uses recipe. By its side is another later and very compendious work which is advertised as containing so many thousand receipts. Still another more recent and even more compendious London book, uses the other word. Both words are right, but which is the better?

.

Several hundred pages of the matter which it is proposed to publish in this column, had been written with the word recipe, according to the observed practice of the majority, but after all it was decided to change it, and for reasons perhaps as immaterial as the difference between the two words in question. Still, the minority side having been taken, it seems best to state the case.

.

A city man, wise in the ways of bread making, was at an old Yankee farmer’s house instructing his housekeeper in the best methods of making home-made Boston brown bread, and used the word recipe frequently. The old man was not illiterate, but excessively old-fashioned, and the trisyllable [sic] annoyed him past bearing. He laid down the Churchman that he had been reading, and leaned back and listened. Then he took off his glasses. Then he began to remonstrate. “Oh, don’t bring those affected city words among us plain people. ‘Recipee, [sic]‘” he repeated, with immeasurable contempt. “My parents always said receipt; my neighbors all say receipt. what [sic] would they think of us if we should go among them putting on such airs as that?”

.

As I overheard this, and a cutting phillipic [sic] which followed, aimed at city affectations in general, my faith in the power of high-sounding recipe to soothe the savage breast was considerably weakened. A long time after, and at a very distant place, a lady school teacher was heard to say: “I am so glad if receipt is the right word instead of recipe; the latter seems so much like a stranger in a foreign dress among our familiar English words of the same dimensions. When I have taught my pupils to indite and recite, it is troublesome to make them understand that recipe is not to be pronounced that way at all, and then, again, to stop them from making two syllables of ripe, wipe, and pipe.”

.

This was another blow at the aristocratic trisyllable [sic], but it seemed hard to have to descend from the lofty heights where it prevailed to the level of the common. Fortunately, just at that time, the great house of the Harpers published the most polite cook-book that has yet appeared. It made extreme correctness of a special feature. It was typographically perfect. It hyphenated every cocoanut [sic]. It split hairs on tea-spoonful. It followed Noah Webster whithersoever he might lead. I twas “the glass of fashion and the mould–I mean mold–of form,” and with all this it adopted receipt instead of recipe.

.

There was no more room for doubt. Higher precedent there could not be, and so, if the reader pleases, as far as this column is concerned, we will render unto the doctors the Latin trisyllable [sic] which is theirs and use only the humbler but safer English receipt.

.

~ The American Pastry Cook, Sixth Edition, published in Chicago by Jessup Whitehead & Co., Publishers, in 1891.

.

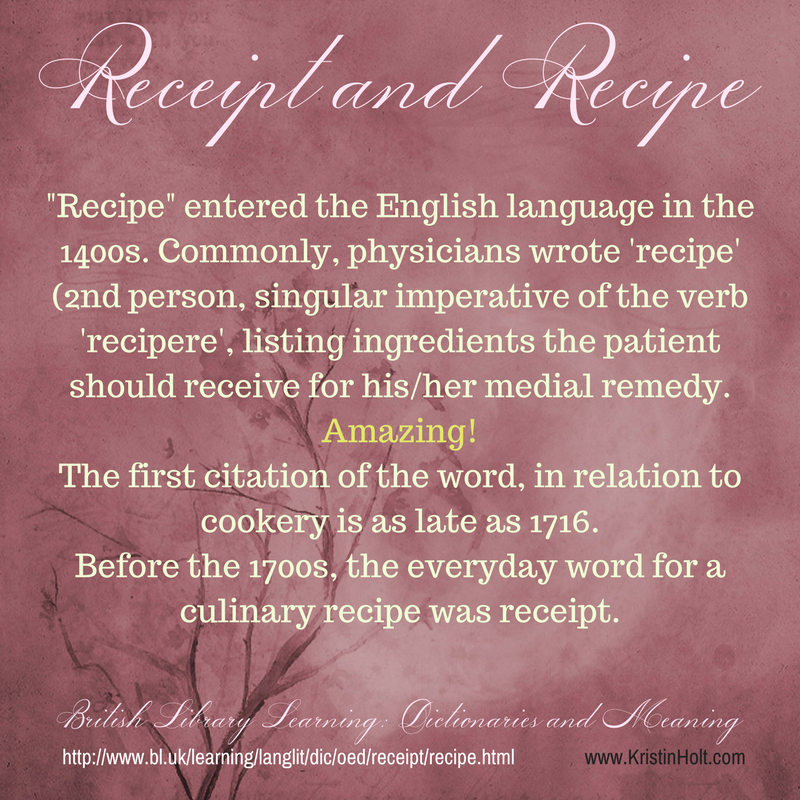

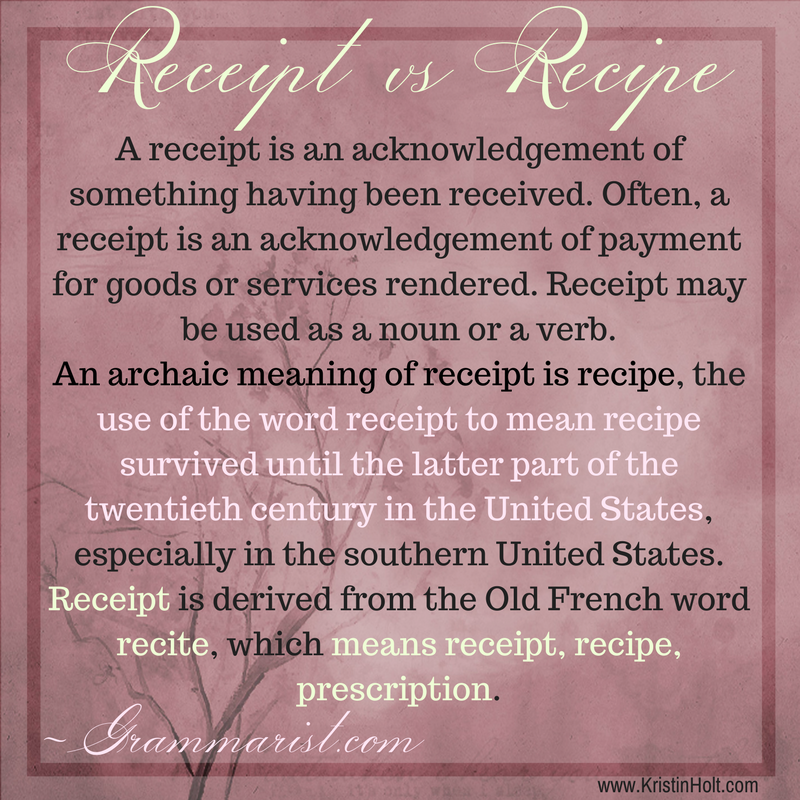

Receipt vs Recipe

Another definition and explanation. Victorian Cooking: Receipt vs Recipe

![]()

Up Next!

Victorian Cooking: Rotary Egg Beater ~ In Time for Angel’s Food Cake?

![]()

![]()

Copyright 2018 Kristin Holt LC