Gingham? Why gingham?

Gingham? Why gingham?

.

![]()

.

Gingham?

.

.

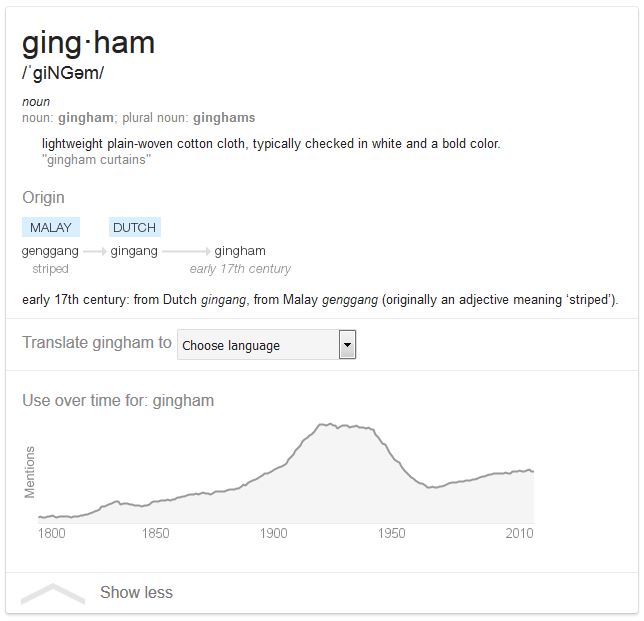

Gingham is a medium-weight balanced plain-woven fabric made from dyed cotton or cotton-blend yarn. It is made of carded, medium or fine yarns, where the colouring is on the warp yarns and always along the grain (weft). Gingham has no right or wrong side with respect to color.

.

…When originally imported into Europe in the 17th century, gingham was a striped fabric, though now it is distinguished by its checkered pattern. From the mid-18th century, when it was being produced in the mills of Manchester, England, it started to be woven into checked or plaid patterns (often blue and white). Checked gingham became more common over time, though striped gingham was still available in the late Victorian period. [Source] (emphasis added)

.

![]()

.

Why Gingham?

.

According to Reference (History), the answer to the question: “What did pioneers wear?” is that “girls’ dresses or skirts and blouses were typically cotton with gingham or calico designs. The girls wore an apron over the outfit and pantalets under it. Women wore simple, floor-length cotton dresses with long sleeves and high necklines.“

.

We know women (or perhaps only young women) wore this basic cotton. But why?

.

I’ll offer several reasons.

.

First, I sew. I know textiles, at least as far as are available today. The difference between natural fibers (cotton, wool, linen) and synthetic (polyester, rayon, spandex, etc.) is familiar. I know from firsthand experience the ease of sewing with natural fibers and how a cotton dress wears. Understanding yardage (how much fabric is required to make a dress) comes with the territory. And price per yard makes a difference.

.

Some fabrics are simply well-suited to work clothes vs. dressy-New-Year’s-Eve-on-a-cruise-ship-only type dresses. Because I’ve sewn since age 11, learned from my mother (who learned from her grandmother), and had a wealth of hands-on experience, I know what fabrics are suitable to what purpose (pants vs. blouse vs. curtains) and can visualize a design or pattern made up in any given fabric–and how it will look on an individual.

.

Pioneer / Frontier / Average people in the Old West needed affordable, durable clothing that would wear well, survive washing after washing, drying in the sun (or heat behind the stove in the winter), repeated ironing, be suitable to the climate and weather. Despite all this, ladies have always wanted to be fashionable and look their best. (Some things–especially about human nature–were no different in Victorian America than they are today.)

.

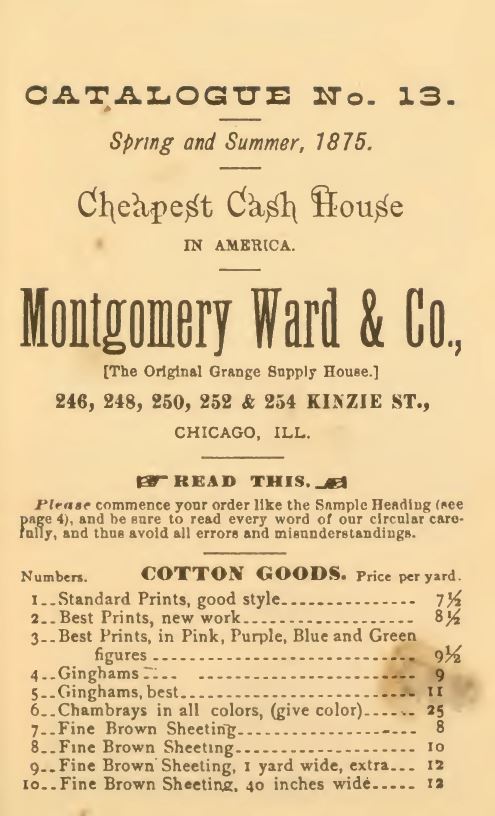

Woven cottons are highly suitable for a dress–and at the high yardage count required to make a long-sleeved, full-skirted (long) dress for a woman, 11¢ (or 4.5¢ by 1895) was a good bargain. The pattern would help hide wear (thinning) and stains an apron failed to prevent.

.

“The most economical cotton dress material that can be bought.” 1895 Montgomery Ward & Co. Catalogue, Spring and Summer.

.

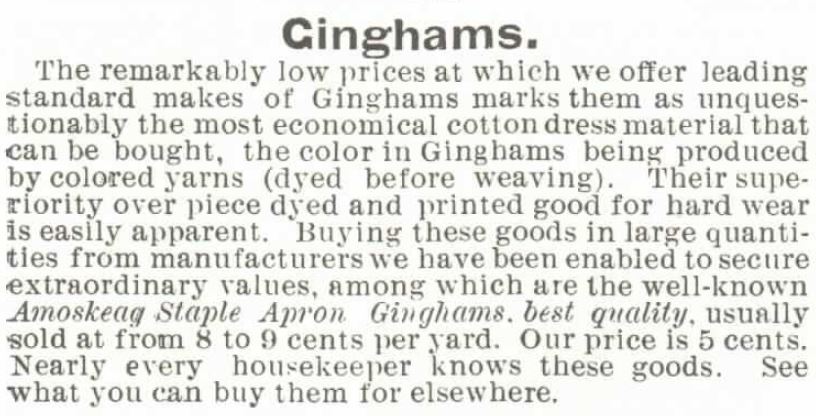

The Montgomery Ward Spring and Summer catalogue of 1875 shows the price per yard (in cents) of various types of fabrics. Two different qualities (probably weights) are listed in the image in numbered lines 4 and 5.

.

Montgomery Ward & co. Catalog No. 13, Spring and Summer 1875, showing cotton goods (including two different weights of gingham) and price (in cents) per yard.

.

This 1875 (reproduction) shows “ginghams” at 9 cents per yard, only slightly more than “standard prints” or “best prints.” Compare to this “chambrays” at nearly triple the cost per yard. Chambray was a cotton fabric used frequently for good men’s shirts and fancier dresses.

.

Chambray, noun: a linen-finished gingham cloth with a white weft and a colored warp, producing a mottled appearance.

.

~ Oxford Languages Dictionary

.

Montgomery Ward Spring and Summer Catalog No. 13, Spring and Summer 1875, showing various fabrics and their price (in cents) per yard.

.

11¢ per yard. Wow.

.

What cost $0.11 in 1875 would cost $2.44 in 2016.

.

.

Examples of today’s cotton gingham, by the yard:

.

The modern article runs 44-inches wide.

.

.

Example of Victorian cotton gingham, by the yard:

.

An antique (circa 1880) gingham (pink and white) listing on eBay, stated the fabric was 26-inches wide.

.

Antique gingham (circa 1880), 26-inches wide. Source: Ebay listing.

.

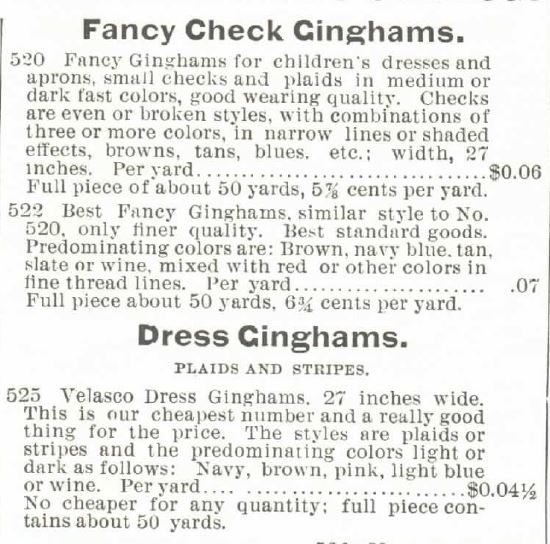

The 1895 Montgomery Ward Spring and Summer Catalogue shows “Fancy Check” and “Dress” ginghams at 27-inches wide. Others at 33-inches wide.

By 1895, the Montgomery Ward company bought textiles in bulk. This strategy allowed them to slash prices to nearly half compared to twenty years earlier:

.

Dress Gingham listings in the Montgomery Ward & Co. Spring and Summer Catalogue of 1895.

.

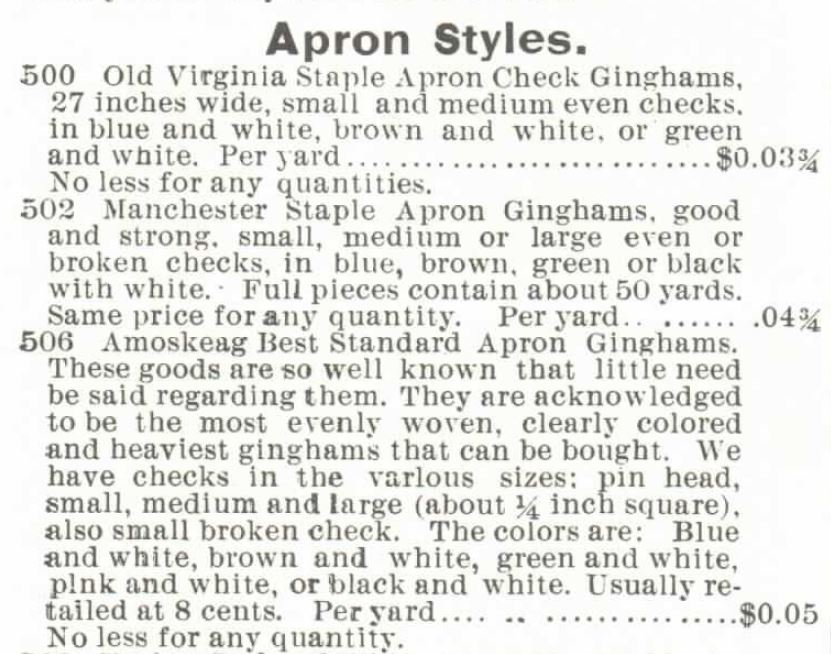

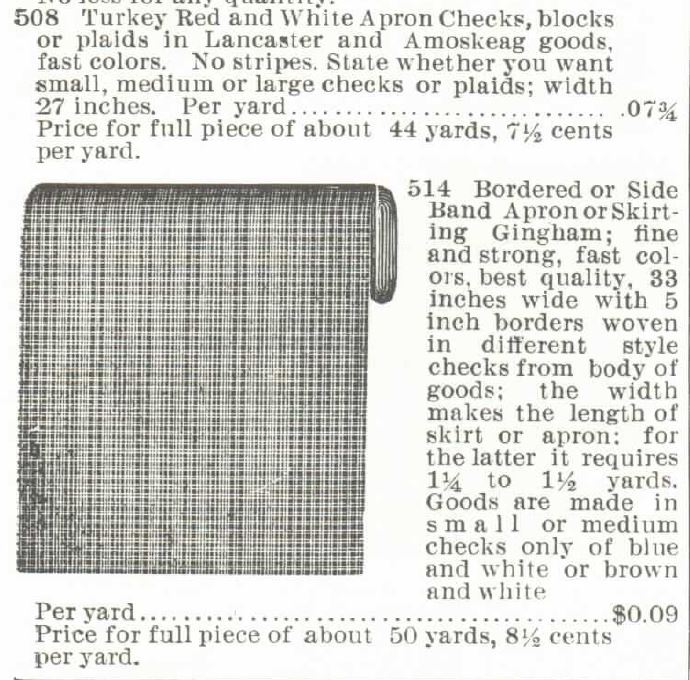

1 of 2: Apron styles of gingham offered in the Montgomery Ward & Co. Catalogue, Spring and Summer, 1895.

2 of 2: Apron Ginghams, Montgomery Ward & Co. Catalogue, Spring and Summer, 1895.

.

More Vintage Advertisements

.

Phillips and Lanoue advertises: “We have just opened a beautiful assortment of French, Scotch and Earlston black and fancy Ginghams, suitable for the season. Also a few pieces of Gingham Lawns.” From Baton-Rouge Gazette (Baton Rouge, Louisiana) on January 2, 1847.

.

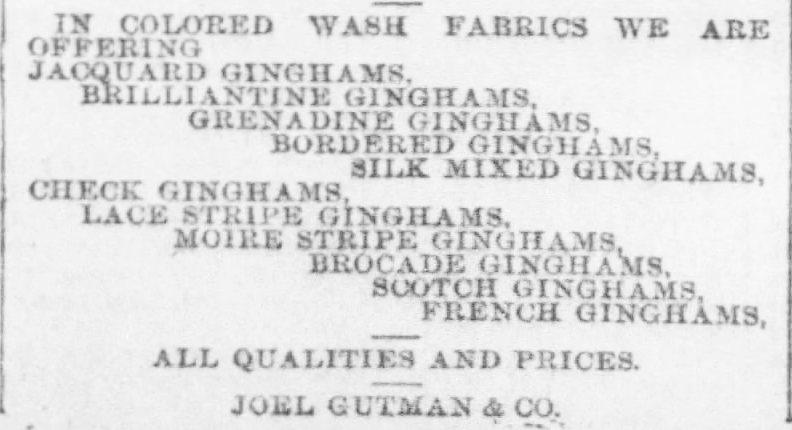

The following ad gives us an idea just how many varieties of gingham existed in Victorian America:

- jacquard

- brilliantine

- grenadine

- bordered

- silk mixed

- check

- lace stripe

- moire stripe

- brocade

- Scotch

- French

.

From The Baltimore Sun of Baltimore, Maryland, March 3, 1890, an advertisement for a wide variety of ginghams, each by name.

.

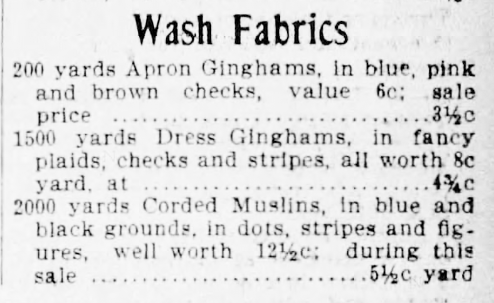

Advertisement for Wash Fabrics, offering ginghams in other patterns (stripes!) and various colors. From Buffalo Evening News of Buffalo, New York, April 3, 1899.

.

.

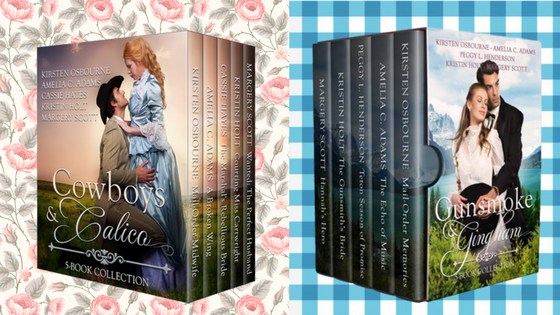

Boxed Sets

.

Last year, 4 out of the same 5 authors published a similarly titled anthology: Cowboys & Calico. Very Old West-sounding and romantic, too. We wanted a title that would match Cowboys & Calico, so we opted to go with another familiar and true-to-history fabric. Cowboys and Gunsmoke definitely put us in mind of the hero, while Calico and Gingham represent the heroine.

.

As both collections were planned as temporary, they are no longer available. Instead, you’ll find individual titles for sale by the authors.

.

.

In my story within Gunsmoke & Gingham, my heroine, Elizabeth, wears a blue checked dress the one day (Independence Day!) she dares move away from her usual plain, drab gray dresses. That blue dress shows her personal decision to take a chance on Morgan Hudson. Additionally, it embodies the possibility of love. The dress is symbolic in more ways than merely color. Elizabeth selected a fabric that was functional, versatile, and infinitely wearable. In comparison, her mother (who plays a significant role in the story) wears (a ghastly) purple silk.

.

I rather like Elizabeth. I hope you will, too.

.

If you’ve not yet read The Gunsmith’s Bride, allow me to introduce you to the characters by sharing with you the opening two chapters. You can read them right here, free!

.

.

![]()

.

Related Articles

See some really cool checked dresses on this book’s Pinterest Board!

The Gunsmith’s Bride has its own Pinterest Board! See images used for inspiration, location photographs, and more!

.

Updated April 2021

Copyright © 2017 Kristin Holt LC