Victorian America’s Gold and Silver Cakes

Victorian America’s Gold and Silver Cakes

.

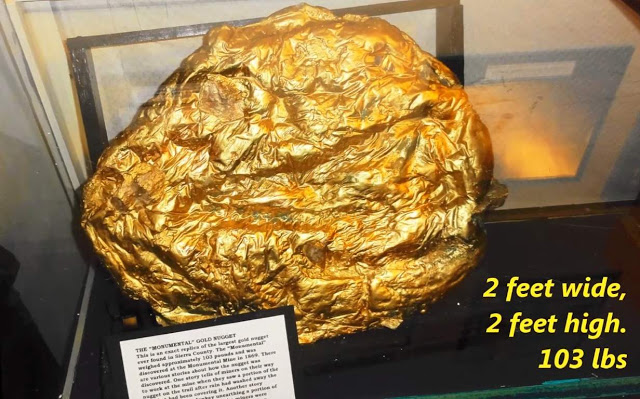

During a century of gold- and silver-fever Victorian America‘s cooks named two similar cakes Gold and Silver. After all, many Americans were keenly aware of the possibility of upward mobility. They desired riches gained by perseverance and sweat of their brow. But if they happened upon an enormous gold nugget, eureka!

.

Gold and Silver: Precious Metals

.

Image: “Monumental,” the largest gold nugget ever found (1869) in Sierra County, on display at Kentucky Mine and Museum. Photo by “funnyaccent” channel on youtube, and posted on Geologyin.com. Note: the museum states the Monumental weighs 106 pounds.

.

America’s gold rush history did not begin with the well-known 1849 California Gold Rush.

Two significant gold strikes occurred in the States earlier in the nineteenth century. First, the Carolina Gold Rush (circa 1800). And the Georgia Gold Rush (1829). In fact, the Georgia strike contributed to the removal of Cherokee Tribes and the “Trail of Tears.”

Other significant gold strikes occurred in North America after the great rush of 1849. E.g., the Colorado Gold Rush, 1858.

Peripherally, I loved listening to this history of the California gold rush. The podcast (2nd image) is unconnected yet superb.

.

.

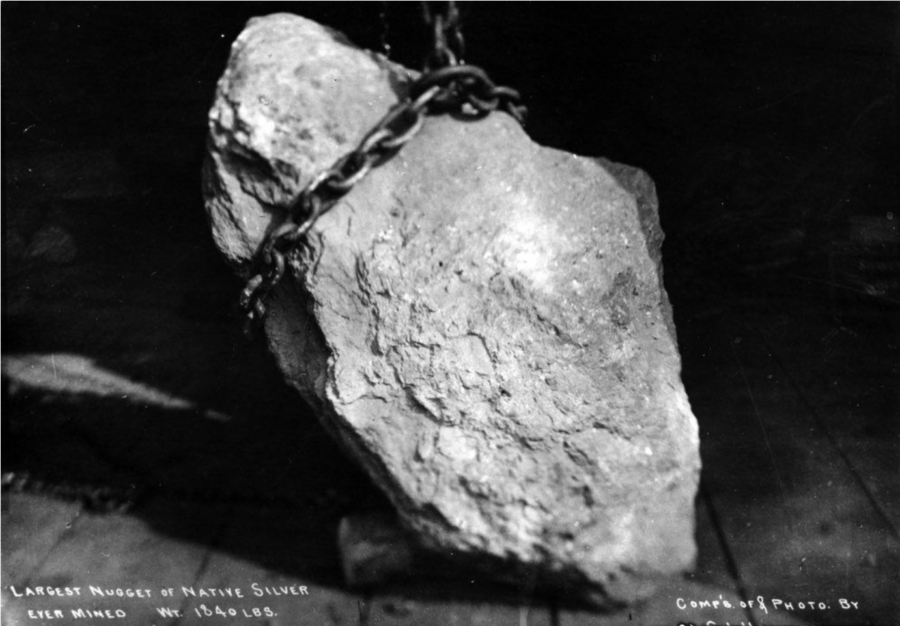

United States silver strikes/rushes of the nineteenth century included:

- Lancaster County, Pennsylvania (pre-Revolutionary War)

- Caroll County, New Hampshire (1826)

- Davidson County, North Carolina (1838)

- Comstock Lode, Nevada Territory (circa 1859)

- Georgetown, Colorado Territory (1864)

- Summit County, Colorado Territory (1864)

- Butte, Montana Territory (1864)

- Park City, Utah Territory (1868)

- Panamint City, California (1873)

- Leadville, Colorado (1874)

- Sierra County, New Mexico Territory (1876)

- Tombstone, Arizona Territory (1877)

- Telluride, Colorado (1878)

- Tonopah, Nevada (1900)

- And many, many more…

.

A large nugget of native silver, mined at Aspen, Colorado, 1894. Image: Public Domain, courtesy of Wikipedia. Vintage script on photograph reads: “Largest Nugget of Native Silver ever mined; Wt 1840 lbs.”

.

.

Gold: Yellow Cake

.

Photo: Raw Egg, with prominent yellow yolk. Image: Public Domain, courtesy of Wikipedia.

.

Victorian Gold Cake, made yellow by various means, was named after the precious metal. Gold cake was made golden by the use of egg yolks (often yelks in vintage recipes). Historic bakers might add yellow tint with safflower, also known as poor man’s saffron or American saffron.

.

Photo: Safflower blossom, Courtesy of Wikipedia, Copyrighted Free Use.

.

Other hints of golden color came from zest of oranges and/or lemons. Common Sense in the Household explains how to obtain flavoring and coloring matter from citrus rind and juice. See the 1884 edition’s recipe, below. Each recipe is presented in chronological order.

.

Silver: White Cake

.

Victorian Silver Cake avoided the yellow tint of Gold Cake by omitting egg yolks and relying exclusively on egg whites. Eggs play an important role in cake baking, thus to omit them entirely wouldn’t yield a fluffy sponge. Bakers whipped egg whites by hand or with a rotary egg beater to incorporate air. The old-fashioned cooks used cuttings from fruit trees as the sap in the sticks would impart flavor to the batter.

.

The wire whisk was invented sometime before 1841.

In the United States, cranked rotary egg beaters became more popular than whisks in the 20th century.

.

emphasis added

.

Separated egg yolks and egg whites. Image Credit: Daniel Peter Ronnenberg, Shutterstock.

.

Victorian Recipes: Gold and Silver Cake

.

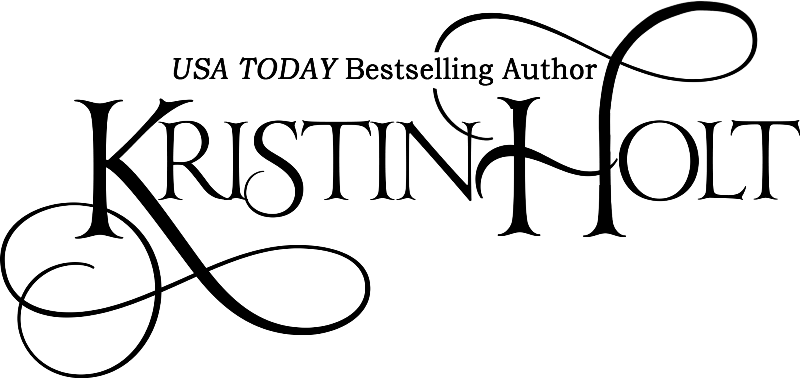

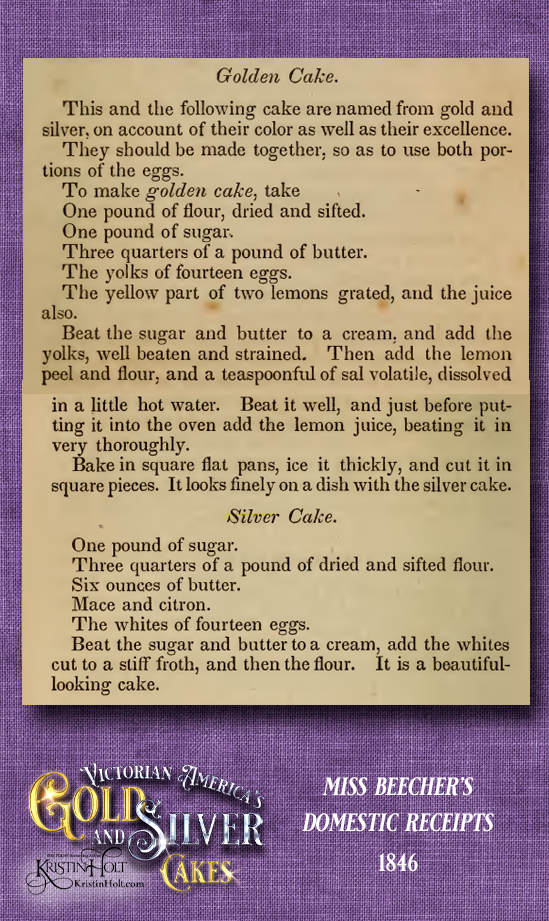

This (Golden Cake) and the following (Silver) cake are named from gold and silver, on account of their color as well as their excellence.

They should be made together, so to use both portions of the eggs.

.

.

Catharine Beecher’s mid-nineteenth century cook book provides an excellent example of Gold and Silver Cake. Her recipe is named Golden Cake, where all other examples offered here are named Gold Cake. Miss Beecher employs a sifter.

This cake is leavened both by the large quantity of eggs and with sal volatile.

.

What is sal volatile?

Baker’s ammonia (ammonium carbonate) is a salt with the chemical formula (NH4)2CO3) is an old fashioned leavening ingredient that pre-dates baking powder and baking soda. Formerly known as sal-volatile or salt of hartshorn. Unlike baking powder or soda, it does not leave an alkaline off-flavor in baked goods.

.

emphasis added

.

Also, sal volatile:

An aromatic alcoholic solution of ammonium carbonate, the chief ingredient in smelling salts.

.

emphasis added

.

Golden Cake and Silver Cake in Miss Beecher’s Domestic Receipts Book, published 1846.

.

Silver or Bride’s Cake

.

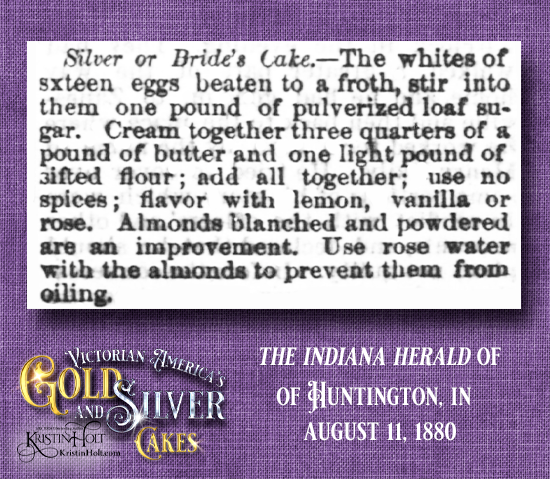

This 1880 recipe for Silver or Bride’s Cake begins much like Angel’s Food Cake, but notice the addition of butter. Angel’s Food contains no fat and the pan cannot be greased. Note the inclusion of blanched, powdered almonds and rose water, or vanilla or lemon.

.

From The Indiana Herald of Huntington, Indiana, August 11, 1880: Silver or Bride’s Cake. Recipe includes tips to prevent almonds from oiling.

.

Leavening agents are necessary for a cake to rise– by creating little bubbles of gas in batter. The above recipe contains no leavening agents other than plenty of eggs while the cake recipes, below, rely on fewer eggs and the addition of baking powder sifted into the flour.

.

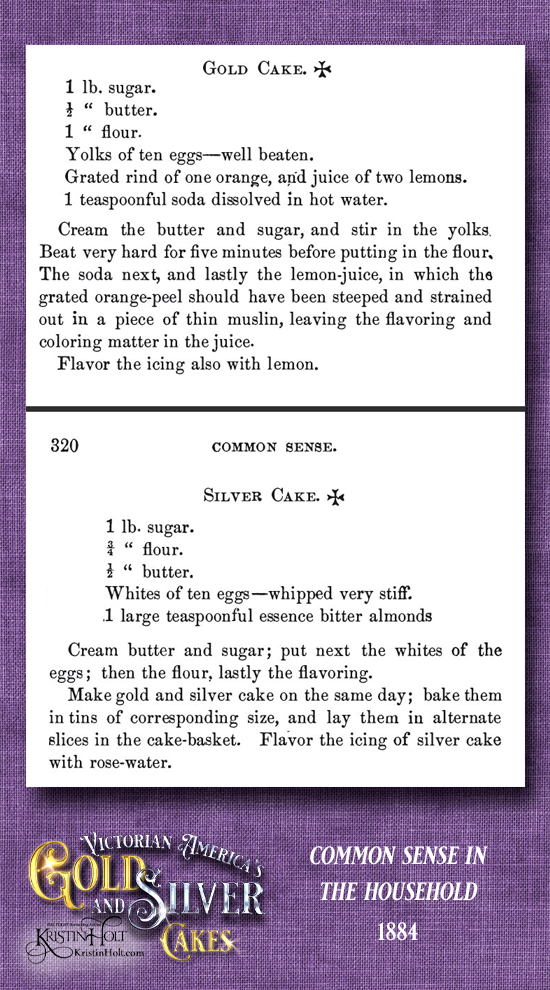

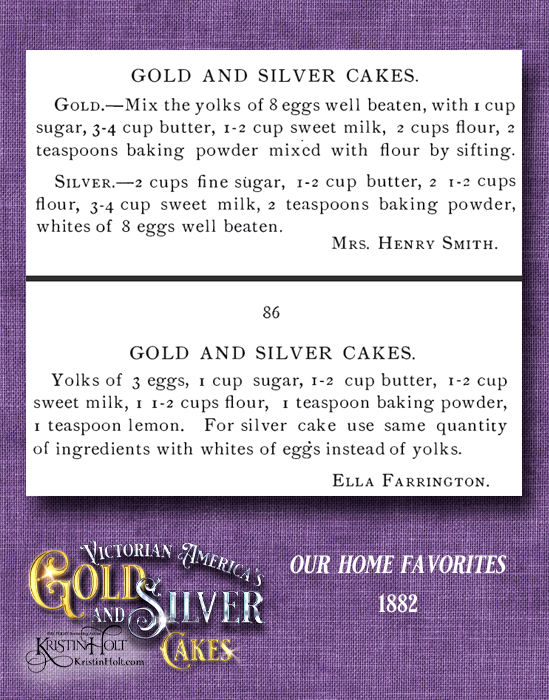

Two pair of Gold and Silver Cake recipes published in Our Home Favorites, 1882.

.

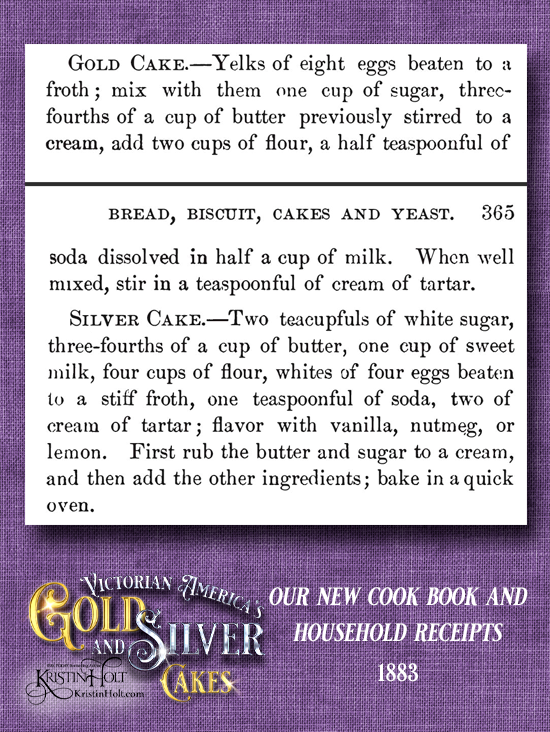

The next pair of Gold and Silver Cakes calls for baking soda rather than powder. [And cream of tartar, too!] Other ingredients and proportions are similar: yolks (yelks), sugar, butter, and milk. Notice that the following Silver Cake recipe gives flavoring options including nutmeg; earlier recipes suggested no spices, only extract (vanilla, rose water, or lemon).

.

Our New Cook Book and Household Receipts, published 1883, with a pair of Gold and Silver Cakes.

.

Gold Cake from Common Sense in the Household, 1884 differs from silver in that it calls for soda and the juice of two lemons. Silver relies on egg whites for leavening. Lemon juice’s acidity reacts with the soda, releasing carbon dioxide, which helps leaven the cake.

.

.

Cream of tartar (also known as cream tartar) is employed in the second set of Gold and Silver Cake recipes, below. Why cream of tartar in cake batter? Another leavening agent in use in America’s Victorian kitchens.

.

.

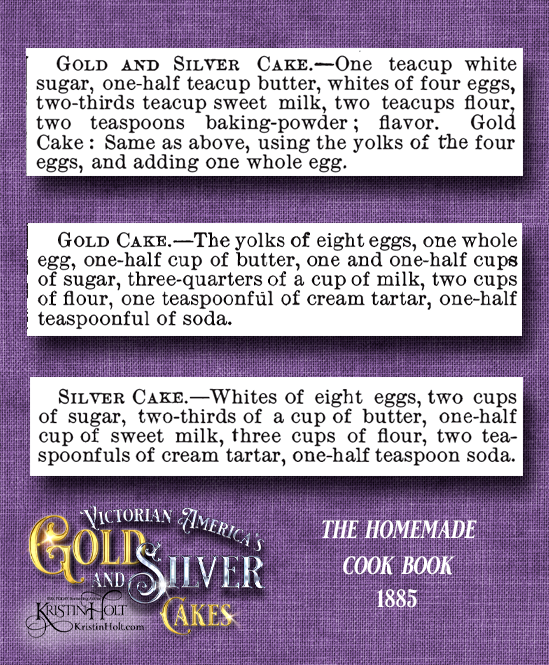

Royal Baking Powder Company published its own recipe book to market its various products. Their Gold and Silver Cakes call for Royal Baking Powder and two extract flavors.

.

.

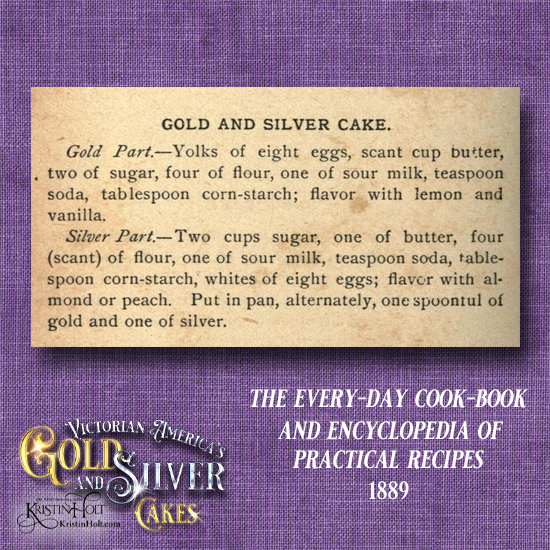

Every Victorian pair of Gold and Silver Cake recipes I’ve seen suggests they be baked together, but apparently served separately. Not layered alternately, and definitely not blended.

Until this 1889 Gold and Silver Cake.

.

Marbled Gold and Silver Cake from The Every-Day Cook-Book and Encyclopedia of Practical Recipes, 1889.

.

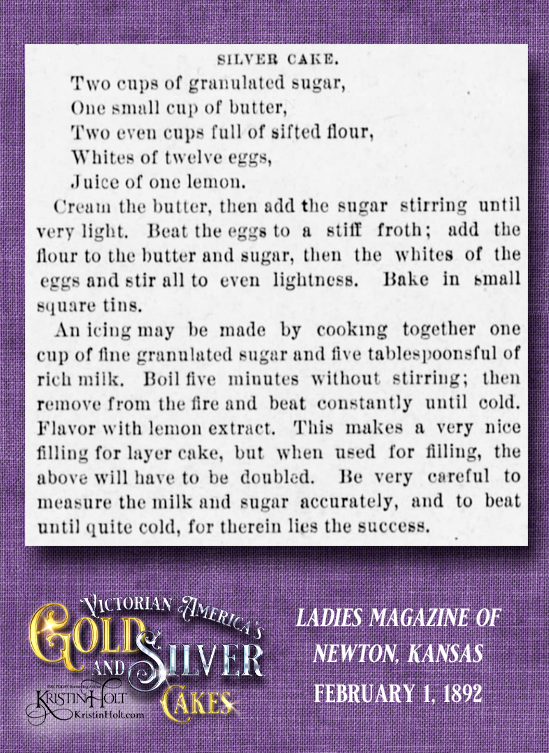

Nineteenth century icing recipes typically required boiling. Some called for egg whites and sugar, where the following calls for sugar and rich milk. The icing is boiled without stirring, then vigorously beaten throughout the cooling process.

.

Silver Cake and icing recipes from Ladies Magazine of Newton, Kansas, on February 1, 1892.

.

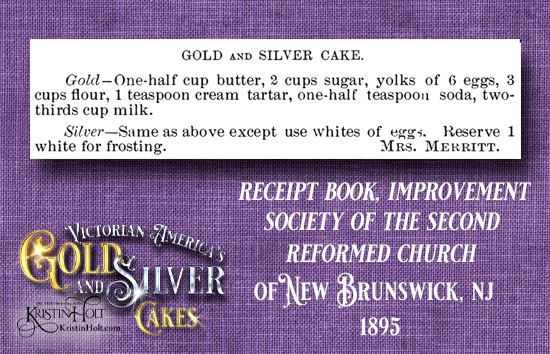

Below, Mrs. Merritt instructs bakers to reserve one egg white for frosting. This is an example of the egg-white-and-sugar boiled icing typically used.

.

Pair of recipes from Receipt Book, Improvement Society of the Second Reformed Church of New Brunswick, New Jersey, 1895.

.

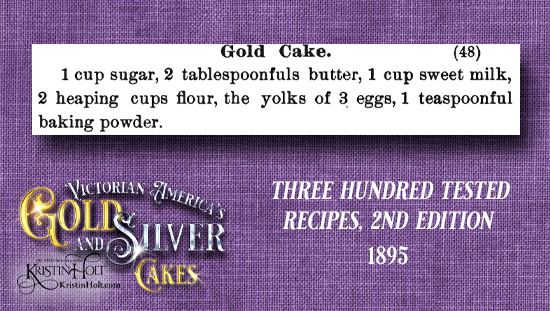

Sometimes Gold and Silver Cake recipes called for comparably few eggs. As an illustration, this 1895 recipe asks for the yolks of three eggs. Surprisingly little, given the above recipes (fourteen)! Why so few? Because baking powder makes up the leavening requirements. Notice how little butter–two tablespoons–where other recipes here wanted as much as one cup!

.

Gold Cake recipe from Three Hundred Tested Recipes, 2nd Edition, 1895.

.

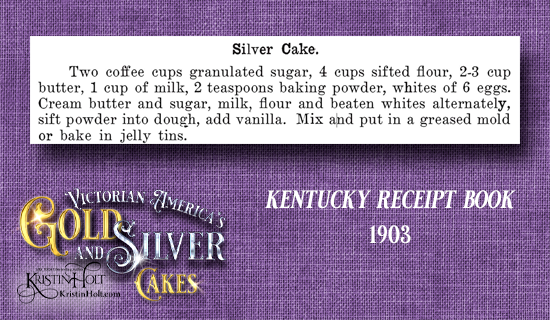

Next, an example of a solo Silver Cake Recipe. Interesting, isn’t it, that Silver Cake did not accompany the Gold?

.

Silver Cake recipe from Kentucky Receipt Book, 1903.

.

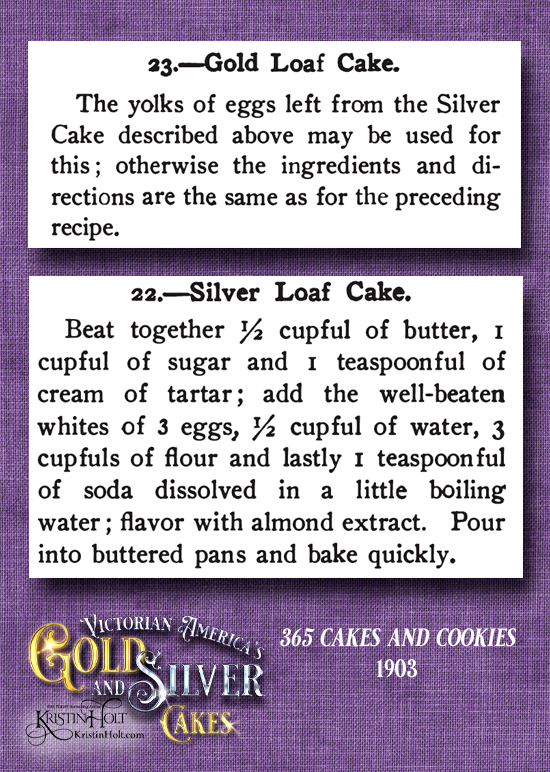

Because the following duo calls for loaf pans, they are unique to this collection.

.

Gold Loaf Cake and Silver Loaf Cake published in 365 Cakes and Cookies, 1903.

.

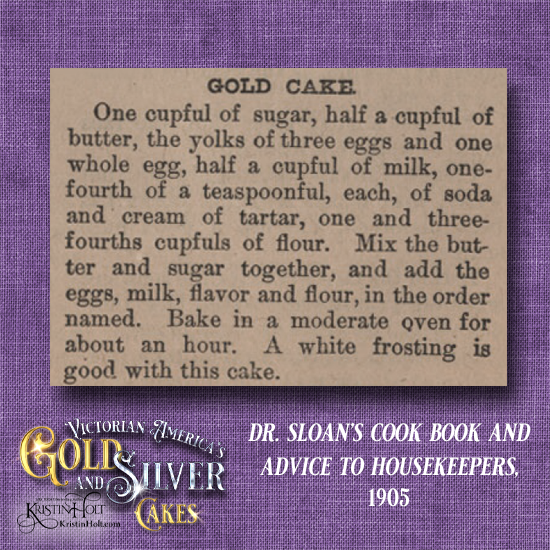

As an illustration of a lone cake, Dr. Sloan’s 1905 publication included Gold but not Silver.

.

Gold Cake from Dr. Sloan’s Cook Book and Advice to Housekeepers, 1905.

.

Invitation

.

Thank you for stopping by and reading about Victorian America’s Gold and Silver Cakes.

What did you notice about this collection of vintage recipes?

Have you baked a homemade yellow cake?

Your thoughts are welcome! Please scroll down and comment.

.

Related Articles

.

.

Copyright © 2021 Kristin Holt LC

Victorian America’s Gold and Silver Cakes